Three Critical Factors for Enabling Community Intelligence

Three Critical Factors for Enabling Community Intelligence

There are moments when, in designing technologies meant to improve our lives, it becomes clear that talking about systems, algorithms, and models is no longer enough. What’s needed is a reflection on the very conditions of coexistence and on the tools through which we construct our worlds.

Building on the themes developed in the original post Community Intelligence, I want to focus on three critical aspects that define this concept and can help us build a more conscious relationship with the digital infrastructures that are increasingly interpreting the world before we even notice it. Every day, we entrust our experience to statistical models, predictive systems, dashboards, and conversational agents that synthesize reality according to opaque criteria. Yet the world we inhabit – its landscapes, languages, conflicts, and rituals – cannot be reduced to data trained on what has already been.

This is why we believe attention must be focused on at least three key issues, for everyone from local administrators and citizens to national and transnational institutions:

- Culturally-aware digital systems

- Continuous and enabling participation

- The social layer in anticipatory governance systems

1. Culturally-aware digital systems

Designing technologies as if there were only one way of knowing the world is not just an engineering mistake—it’s an epistemic one. Every culture articulates knowledge, technique, and meaning in unique ways. Technologies are never neutral or universal: they are built within and through specific worldviews. Yet much of today’s digital infrastructure— from public service interfaces to decision-making algorithms—operates through simplification, removing or ignoring the multiplicity of meanings.

This also applies to artificial intelligence systems, which are often trained on datasets that reflect dominant, Anglo-centric, and already-consolidated perspectives. The result is a progressive semantic dilution, leading to the erosion of vital cultural, linguistic, and symbolic references.

To counter this, we must develop culturally-aware digital systems. This entails at least three strategic layers:

- Situated data policies: Data is not raw material but a cultural artifact. We must define local rules for data collection, management, and reuse—rules that respect the informational sovereignty of communities and their right to be represented accurately.

- Model retraining: Models must not remain frozen. We need continuous updating processes that integrate emerging knowledge, local dialects, lesser-known histories, and non-standard forms of knowledge.

- Data federation: Rather than centralizing everything, we should foster distributed networks of exchange and interoperability across territories, where each node preserves its own semantic specificity.

This process cannot be implemented uniformly or instantly. It must be built as a progressive and adaptive journey, tailored to each territory’s actual resources and organizational capacity. That’s why Relaia promotes tools like Local Protocols: participatory processes for developing shared, revisable, and operational guidelines that help translate local needs into concrete technical requirements.

2. Continuous and enabling participation

Digital systems designed for the public should not be imposed from above but co-constructed. Participation can no longer be reduced to occasional consultations or formal involvement rituals that often occur when decisions have already been made “elsewhere.”

We need a new deliberative infrastructure: continuous, plural, and enabling participation.

This means reimagining territorial governance so that citizens, stakeholders, and institutions are actively and continuously involved in problem interpretation, priority setting, and solution evaluation.

This is realized through:

- Digital tools for continuous consultation that collect opinions, concerns, visions, and experiences in a distributed and scalable way;

- Hybrid methodologies (in-person + digital) that leverage the relational intelligence of groups, oral knowledge, and the embodied context of decisions;

- Radical listening mechanisms that go beyond “feedback collection” and instead translate what emerges into operational criteria guiding parameters, metrics, and policies.

This participatory infrastructure must also shape the very technologies used by public administrations: algorithms, dashboards, and digital twins should be designed to maintain an ongoing dialogue with communities. Without this connection, even the most advanced platforms risk becoming self-referential black boxes, unable to learn or adjust course.

3. The social layer in anticipatory governance systems

In advanced governance systems—such as urban digital twins, environmental predictive models, and smart city dashboards—the social dimension is often treated as noise or, at best, secondary data. But without incorporating lived perception, relational dynamics, and experiential insight, every model remains blind to reality.

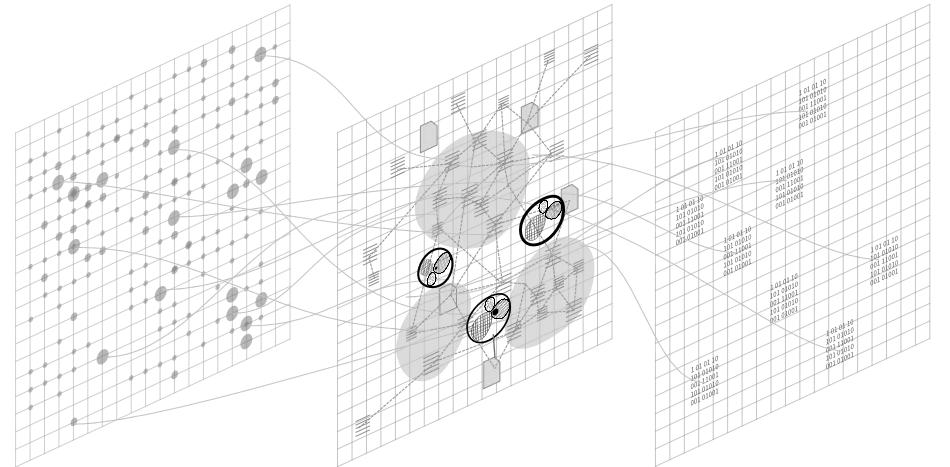

This is why, in line with long-standing research, we advocate for integrating an explicit social layer into anticipatory systems: a layer capable of capturing and analyzing not just physical and quantitative data, but also the relationships, conflicts, emotions, and imaginations that animate a territory.

This is the core of our work in Relaia Insight: transforming inputs from civic engagement and stakeholder consultation processes into structured, semantically rich data readable by predictive models. We use research-based tools like Systemic Relational Cues (Spunti Sistemici Relazionali) to map connections between narratives and policy domains, giving a dynamic and contextual view of the territory.

These data streams flow in real-time into digital twins, informing urban, environmental, and infrastructural decisions. Simulation becomes not an abstract act but a reflective mirror of living social complexity, capable of anticipating scenarios but also of evolving based on emergent territorial signals.

Intelligence is not a property of models, but a function of relationships. It does not emerge by compressing diversity, but by amplifying it. And the digital realm—if it is to be a generative tool for the future—must become a technology of plurality, coexistence, and counter-temporality.

The three critical factors I’ve described are not universal solutions, but operational coordinates for building a radically situated approach. An approach that sees territories not as obstacles to scalability, but as the primary source for adaptation, innovation, and collective desire.

In a time when we risk being trapped in the latent space of algorithms, the challenge is to return to inhabiting real worlds—those fragile, imperfect, but deeply meaningful worlds that surround us.

And it is there that community intelligence can take root.

Related Posts

Other articles you might find interesting

Community Intelligence

Community Intelligence is a holistic approach to developing digital ecosystems where collective and digital intelligence coexist, fostering local autonomy and collaboration.

Systemic Relational Insight

Today's interconnected world requires new forms of collective intelligence. Systemic Relational Insights (SRI) is a new method that combines human input with algorithmic support to analyze and understand socio-technical-natural systems.

Did you like this content?

Leave us your email if you want to receive them fresh from the press. We will only use your email for this purpose